The occasion of Pakistan Prime Minister Yusuf Gilani’s official visit to China was an opportunity for both parties to stake a claim to a post-United States future as the closest of allies, with a shared commitment to a stabilized Afghanistan and recovering Pakistan.

Chinese state media gave spectacular coverage to the visit as a sign of its geopolitical significance. The Chinese government contributed to the sense of occasion with the kind of gesture the Pakistani military – smarting from the humiliation of the killing of Osama bin Laden by American Special Forces inside Pakistan – appreciates the most: a promise to expedite delivery of 50 Chinese fighter jets.

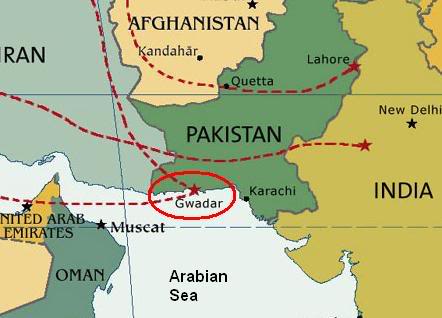

Then Pakistan’s Defense Minister Ahmed Mukhtar put his hoof in it:”The Chinese government has acceded to Pakistan’s request to take over operations at Gwadar port [in Balochistan province] as soon as the terms of agreement with the Singapore Port Authority (SPA) expire,” Associated Press of Pakistan (APP) quoted Defense Minister Chaudhry Ahmad Mukhtar as saying in a statement.

According to APP, Mukhtar said Pakistan appreciated that the Chinese government agrees to run the port, but would be more grateful “if a naval base is constructed at the site of Gwadar for Pakistan.” [1]His remarks set off alarm bells around the world, as pundits dusted off the “string of pearls” analogy describing China’s alleged efforts to create a network of military-ready ports, and raised the specter of the Chinese dragon bathing his vermilion claws in the milk-warm waters of the Indian Ocean.

China promptly issued a denial – about building the naval base, at least – that made the whole episode look like another spasm of incompetence by President Asif Ali Zardari’s administration. [2]

It also forced China’s quasi-official nationalistic mouthpiece, Global Times – which had uncritically picked up on the Associated Press of Pakistan report – to do some backtracking, backfilling and blustering:Beijing recently denied a rumor that the Pakistani government has invited it to build a naval base at the port of Gwadar.

But this doesn’t stop some of the Western countries and India, China’s regional competitor, playing with the so-called China threat theory.

[I]f the world really wants China to take more responsibilities in Asia-Pacific region and around the world, it should allow China to participate in international military co-operations and understand the need of China to set up overseas military bases.Peace is China’s only military interest and the international community should keep this in mind. [3]It looks like Mukhtar badly overreached in his attempt to convince the administration of US President Barack Obama of China’s willingness to replace the US as Pakistan’s official best friend forever.

It may simply be that he was just trying to be helpful, and get Pakistan out of an embarrassing jam on the operation of Gwadar.

There are three likely reasons and one unlikely reason why China has little interest in helping Pakistan play the Gwadar card, either as a commercial or military property.

The unlikely reason was floated by The Times of India. It linked the port project to the attack by militants on the Mehran naval base in Karachi this week, apparently in an attempt to publicize the fact that Chinese engineers are assisting the by now globally unpopular Pakistani military:Apparently jolted by the Taliban attack on Pakistan’s naval base, China on Tuesday indicated it would not invest funds on creating another naval base in that country. [4]The linkage between the two events probably does not extend beyond the shared use of the three words “naval base” and “China”.

As we shall see, deadly peril is a fact of life for Chinese personnel at Gwadar already. China would be unlikely to reverse a major strategic decision because 11 Chinese helicopter technicians were in transitory peril more than 1,000 kilometers from Gwadar during an attack intended to embarrass the Pakistani military and destroy two US surveillance planes as retaliation for the raid that killed Bin Laden.

As for the likely reasons for Chinese wariness:

First and foremost, Gwadar is a failed commercial port – built with over US$200 million in unenthusiastic Chinese aid – in the middle of a wilderness that nobody visits. [5]

In the most recent court case that has bedeviled the port and its operator – Port of Singapore Authority or PSA – it was alleged that the only way to get business to Gwadar – for what purpose and to whose benefit it can only be imagined – was to divert cargo from Karachi:Since PSA has failed to attract commercial vessels to Gwadar Port, it is reported and in common knowledge that the government at the expense of the public exchequer is subsidizing and artificially creating business for PSA by diverting different cargoes of urea and wheat (otherwise destined for the ports at Karachi) to Gwadar Port which reportedly resulted in a loss of at least Rs 2,500 [US$40] per ton in extra, unnecessary and unwarranted costs to the public exchequer. PSA has failed to make any investment in additional facilities at Gwadar Port contrary to the tall claims at the time of award of the CA to PSA, it added. [6]The cash-strapped Pakistani government apparently reneged on a deal to develop a free-trade zone at the port, ditched plans to build transportation infrastructure connecting the port to the interior, and failed to follow through on a no-cost transfer of developable land at the port to the operators. The unhappy operators, PSA, have been subjected to accusations of non-performance it dismissed as unfounded, and harassing lawsuits inspired, it alleges, by interests from the competing port of Karachi.

Pakistan’s Supreme Court has instructed the Gwadar Port Authority to cancel PSA’s concession. If a new operator could be enticed into taking over the port, it is extremely unlikely that PSA would insist on serving out its contract until 2047.

Pakistan is understandably keen to find a new operator pronto for the troubled commercial port.

China has been floated as a potential replacement for PSA virtually since the inception of the contract, long before Mukhtar’s statement; but China is unlikely to be enthusiastic about taking the port off PSA’s hands except as an expensive favor to Pakistan.

It would not only take an immense expenditure – perhaps $2 billion – to link Gwadar to inland economic centers in Pakistan, western China and Central Asia; the effort would be largely zero-sum for Pakistan, taking business away from Karachi. The strategic justification for China – that Middle East crude could be landed at Gwadar, thereby avoiding the perils of the Straits of Malacca, and pumped or trained over the Himalayas at a capital cost of $30 million per kilometer in the more difficult stretches – seems more Pakistani wishful thinking than China’s planning. [7]

Mukhtar might have been trying to sweeten the bitter commercial pill of taking over the commercial port by dangling the prospect of an advantageous cooperation between Islamabad and Beijing on a naval base.

He also may have been trying to placate the Pakistani navy at the same time by building a base for it at Gwadar, since the navy’s reported unwillingness to surrender 582 acres (236 hectares) of prime land have been cited as a key obstacle to happy and harmonious development of the port. [8]

He also may have been trying to placate the Pakistani navy at the same time by building a base for it at Gwadar, since the navy’s reported unwillingness to surrender 582 acres (236 hectares) of prime land have been cited as a key obstacle to happy and harmonious development of the port. [8]

If so, Mukhtar’s brainstorm, instead of pleasing everyone, will probably end up pleasing no one – especially the Chinese.

Which brings us to the second explanation for Beijing’s lack of enthusiasm.

China is attempting to promote American military retreat from Afghanistan, and a reduced US security footprint in Central and South Asia. Showcasing Sino-Pakistani ties was supposed to serve as a declaration that the region’s priorities were shifting from a massively destabilizing war effort led by the United States to an infrastructure and social development effort supported by China to the benefit of Pakistan as well as Afghanistan.

Raising the possibility that China was going to militarize Gwadar provided the US with an incentive to stick around and work out the kinks in its military relationship with Pakistan, instead of pulling up stakes.

The Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs categorically knocked down the naval base story, as Dawn reported:BEIJING: China said on Tuesday that it had not heard of Pakistan’s proposal for China to help it build a naval port at the deep water port of Gwadar.

“Regarding that specific cooperative project, I have not heard of it,” Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Jiang Yu told a regular news briefing in Beijing.

“It’s my understanding that during the visit last week this issue was not touched upon,” she said. [9]Thirdly, Gwadar is in Balochistan … and Balochistan is a loaded gun at the head of Pakistan and China that will go off if either country tries to make geostrategic hay with the port.

Pakistan’s army seized Balochistan in 1948. Through five different bouts of hot insurgency and martial law, Pakistan asserted control over the region – and maintains control today – with its usual combination of brutality, incompetence and smug indifference, allegedly disappearing, torturing and murdering any Balochi leader of stature.

The entire province only has 6 million people – in a nation of 170 million – and their concerns and priorities are largely swept aside by the Pakistani government.

The Balochistan vibe is something along the lines of Afghanistan with an ocean view: mineral wealth, violence and resentment. Independence sentiment, or at least, independence rhetoric, is a staple of Balochi discourse.

In a similar but more subtle replay of the “you say Myanmar, I say Burma” clashing nomenclatures, “Balochistan” is the official name of the Pakistani province; “Baluchistan” is frequently the preferred spelling for independence advocates.

Supporting Balochistan independence is also something of a cottage industry among strategic thinkers in the United States.

Their motives are rather transparent – unless one believes that ardent support of Balochi independence can be reconciled with utter neglect of the aspirations of that other land of the dispossessed, the one that happens to be administered by India: Kashmir.

An independent Balochistan would be another case of substandard American nation-building, along the lines of Kosovo and Southern Sudan. But it would, like them, serve a negative purpose: weakening a disliked regime and denying a significant strategic asset to a competing power.

Independent Balochistan would achieve a trifecta of sorts. In addition to discommoding Pakistan and China, it would encourage agitation for independence across the Pakistani border among the Balochis of eastern Iran.

To support the independence of Balochistan – which would involve a radical dismemberment of Pakistan – a supporting narrative to merge the Baloch and anti-terror themes has been created to delegitimize the Pakistani state and challenge its right to territorial integrity. It goes like this:

The extermination of Islam-tinged terrorism is the world’s existential errand in South and Central Asia.

Pakistan is infected with the radical Islamist virus.

By this framing, Pakistan is said to have two – and only two – alternatives.

One is to engage in a civil society revolution to root out extremists and the military-security complex that shelters them. This scenario is predicated upon rapprochement with a benevolent and generous India to knock the ideological, economic and national security props out from under Pakistani hardliners – and their Chinese enablers – and remake Pakistan as a vibrant, multi-ethnic democracy.

As Pakistani scholar Hami Yusuf articulated the position:Policymakers have long acknowledged that the only way to ensure South Asian peace and prosperity is by normalizing relations between Pakistan and India. The chances for boosting trade, cooperating in Afghanistan, launching water- and energy-sharing projects, and eventually addressing disputed borders and transnational threats such as climate change are extremely low if Pakistan and India remain locked in an arms race spurred by Chinese contrivance. [10]As the outpouring of official Pakistani satisfaction with Gilani’s visit shows, the position described by Yusuf is not yet a “policymaker” consensus – unless vast swaths of the Pakistani and Indian military and security apparatus are excluded from the definition. For that matter, better to exclude the Pakistani people as well.

The most recent Pew poll of Pakistani attitudes – released in July 2010 – reported that India was regarded as the “greatest threat to Pakistan” by 53% of respondents. That’s compared to 23% who named the Taliban. [11]

Pakistani civil society may be disgusted with its spooks and generals and their antics – like the accusation by ex-Inter-Services Intelligence chief and alleged de facto Taliban asset Hamid Gul that the United States carried out the Mehran raid – but consigning the country’s future to the tender mercies of India – is still a hard sell.

That leaves the second alternative: Pakistan is relieved of its Islamist extremist problem by shedding its border regions – and

its militants – through some internationally imposed disassociation, something that is, with a straight face, referred to as “peaceful Balkanization”.

A notorious map published by Lieutenant Colonel Ralph Peters in the Armed Forces Journal in 2006 provided a picture of what a Balkanized Pakistan would look like.

Independent Balochistan would be a sizable rectangle composed of about 50% of current Pakistani territory – and a sizable chunk of Iran. For good measure, Peters envisioned Pakistan losing its Pashtun west to a muscled-up Afghanistan and dwindling to a narrow territory on either side of the Indus River. [12]

For the Obama administration, the attractions of presiding over the dismemberment of Pakistan have taken a back seat to obtaining the help of its security and military apparatus in finding a way out of the Afghan mess.

However, as the United States looks to wind down its involvement in Afghanistan and has less incentive to overlook Pakistan’s inadequacies as an ally, the “let Pakistan go down the drain” faction may get a more favorable hearing.

The Balochistan independence movement is ready to assist.

The Baloch Conference of North America held a meeting in Washington at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace on April 30, 2011. It issued a declaration describing the horrors of the Pakistani occupation.

Going beyond the issue of Balochistan, the declaration characterized Pakistan as not being “a truthful and trusted ally in the war on terror” (making the prescient assertion, prior to the notorious raid to kill Bin Laden in Abbottabad, that “Bin laden, [his deputy] Aymen al-Zawahiri and [Taliban leader] Mullah Omar … are still hiding in Pakistani sanctuaries provided to them by Pakistani military and its ISI”).

In article 8, the declaration stops pussyfooting around to declare:This Conference considers Pakistan a terrorist state and asks the UN and the International Community to declare her as such.Article 13 ties the various strands together and declares:This Conference calls for a peaceful balkanization of Pakistan on ethnic and linguistic and cultural lines to eliminate and eradicate Islamic extremism and terrorism once and for all. This Conference rejects the artificially drawn British boundaries of the Durand line and Goldsmith line and demands the redrawing of the map of the region based on ethnic, linguistic and cultural lines. [13]Linking Baloch independence to the war on Islamist extremists may appear to be an attractive, low-cost way to entice the United States into stirring the pot.

However, in practice “peaceful Balkanization” would probably look a lot more like a perpetuation of the miserable, expensive counter-insurgency the US has been conducting in Afghanistan and Pakistan for the past 10 years.

In February, before a Chinese-built naval base at Gwadar was even a glint in Ahmed Mukhtar’s eye, Selig Harrison sounded the twin clarions of Balochi independence and the “war on terror” in an op-ed in the National Interest:[T]he United States should do more to support anti-Islamist forces along the southern Arabian Sea coast. First, it should support anti-Islamist Sindhi leaders of the Sufi variant of Islam with their network of 124,000 shrines. Most important, it should aid the 6 million Baluch insurgents fighting for independence from Pakistan in the face of growing ISI repression. Pakistan has given China a base at Gwadar in the heart of Baluch territory. So an independent Balochistan would serve US strategic interests in addition to the immediate goal of countering Islamist forces. [14]Great Game On!

On a demographic note, the entire Baloch population of Balochistan is only around 6 million. It is questionable that every one of them qualifies as an “insurgent” in open rebellion against the Pakistani state. Whether or not every man, woman and child in Balochistan is an insurgent, the sense of grievance against Islamabad is strong and genuine.

And, because they are seen as Islamabad’s partners in penetrating and exploiting Balochistan, the Chinese are not popular there either.

The rhetoric of Balochi politics is dominated by resource nationalism of the sort that would receive short shrift from the United States and the international business community if it were invoked by the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and not voiced by a group much inclined to do the West a geostrategic favor in Pakistan.

Balochi politicians are agitating against Chinese investment in a copper and gold mine at Sendak as an Islamabad-coordinated raid on the region’s riches.

On the issue of Gwadar, the provincial government has made the rather dubious claim that the key to success of the white elephant port is not massive investment to link it to Central Asian markets, but the exercise of professional Balochi management.

Asserting that former president Pervez Musharraf had slow-walked construction of Gwadar not because it was an immensely expensive boondoggle in the desert but because he wanted to delay Balochi enjoyment of this mercantile gold mine, the provincial government called for cancelation of the 40-year contract by PSA, and takeover of the contract by local interests.

When the first report of the alleged Chinese takeover of Gwadar hit the Pakistani papers, the provincial chief minister, Nawab Muhammad Aslam Raisani, who is also chairman of the board of directors of Gwadar Port, rushed to Islamabad to object to getting blindsided on the announcement and press the case for local, instead of Chinese, management. [15]

Under the rubric of forestalling “Panjabi-Han” infiltration, warnings – or unsubtle threats – to the Chinese to steer clear of the region are familiar themes in Balochi politics.

As an editorial, “Balochistan for Sale”, in an online Balochi journal put it:It is extremely disturbing the way Islamabad unilaterally decides the fate of certain mega projects and lands inside Balochistan without even the consent of the local stakeholders. Foreign investment is one thing but deciding the future a controversial project is another thing.

Such secret deals will only antagonize the local people of the conflict-driven province. In the past, Baloch armed groups had attacked and killed Chinese engineers because of the same reason. If Islamabad does not consult the Baloch and proceed with these high level deals, it is going to irresponsibly compromise the safety of the Chinese. The security of foreign nationals would further be jeopardized if Islamabad annoys the government of Balochistan too. [16]The idea that China would find itself exposed to the same kind of savage insurgency that bedevils the United States in Iraq and Afghanistan is not, I suspect, unwelcome to American pundits.

Robert Kaplan, the Atlantic security columnist, has adopted Gwadar-as-linchpin framing and frequently returns to the theme of Baloch insurgents turning the province into a sea of sandy fire for unwelcome outsiders. He interviewed a Baluch nationalist, who told him:”No matter how hard they try to turn Gwadar into Dubai [in the United Arab Emirates], it won’t work. There will be resistance. The pipelines going to China will not be safe. They will have to cross through Baluch territory, and if our rights are violated, nothing will be secure.” In 2004, in fact, a car bomb killed three Chinese engineers on their way to Gwadar. Other nationalists have said that Baluch insurgents would eventually kill more Chinese workers, bringing further uncertainty to Gwadar. [17]Several Chinese engineers have died in attacks around Gwadar and security was cited as one of several reasons why the Chinese pulled the plug on plans for a 200,000 barrel/day refinery at Gwadar.

There are nagging rumors that the Balochi separatists are receiving assistance from the US Central Intelligence Agency, India’s Research and Intelligence Wing, and even Russian intelligence as part of their ongoing support for the anti-Taliban Northern Alliance in Afghanistan, and to punish Pakistan for its pro-Taliban Afghan policy.

Asia Times Online’s Pepe Escobar has made the case for Gwadar as the key objective in the battle of Pipelineistan – US efforts to block the Iran-Pakistan (and maybe India) natural gas pipeline – in favor of the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India (TAPI) pipeline bringing in the stuff Pakistan so desperately needs through Afghanistan from Central Asia. [18]

On her blog, Dr Stuart Bramhall retailed some of the accusations of foreign involvement in training Balochi insurgents – which are indignantly denounced by Baloch advocates – while echoing the pipeline them.[The United States, India and Russia] support Balochistan independence, owing to the province’s strategic importance as an energy transit route. Not only is it a conduit for the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India oil pipeline (which is mostly non-functional because the Taliban keep blowing up the Afghanistan section) and the planned Iran-Pakistan-India natural gas pipeline, but more importantly it adjoins the Arabian Sea and the Straits of Hormuz, which annually transship 30% of the world’s oil resources pass every year. [19]In any case, to the Chinese, Gwadar spells bad economics, premature geostrategic confrontation with the United States and the prospect of becoming the target of a burgeoning local insurgency that just might be receiving covert support from Washington and New Delhi.

However, if China decides to play the long game on Gwadar, and shoulder the burden and risks of operating the commercial port, a port call by Chinese naval vessels – and, later on, the oft-rumored naval base – may indeed be in the cards.

Notes

1.